Since the first trams appeared on the streets of Calgary, the city’s transportation system has changed many times to meet its demographic and innovative challenges. In a sense, urban transportation has shaped the social landscape and lifestyle unique to Calgary. In general, the transport system here is quite simple. Read more about the history of Calgary public transportation at calgary-future.

Backstory

In 1893, the city signed a contract with the Calgary Street Railway Company to build a street railway system. However, a year later, the company refused to implement the project due to financial difficulties. The city returned to this idea again in 1901 and 1904, but no concrete steps were taken.

Things got better in 1906, when Calgary’s population grew by nearly 200% over 1901. Then a local entrepreneur launched his own private transport system using horse-drawn omnibuses. Later, a second private transport business was launched: the Calgary Car company used buses with solid rubber wheels for three months. Neither this nor the previous business was successful, so in April 1907 the city approved the construction of tram tracks.

The first trams

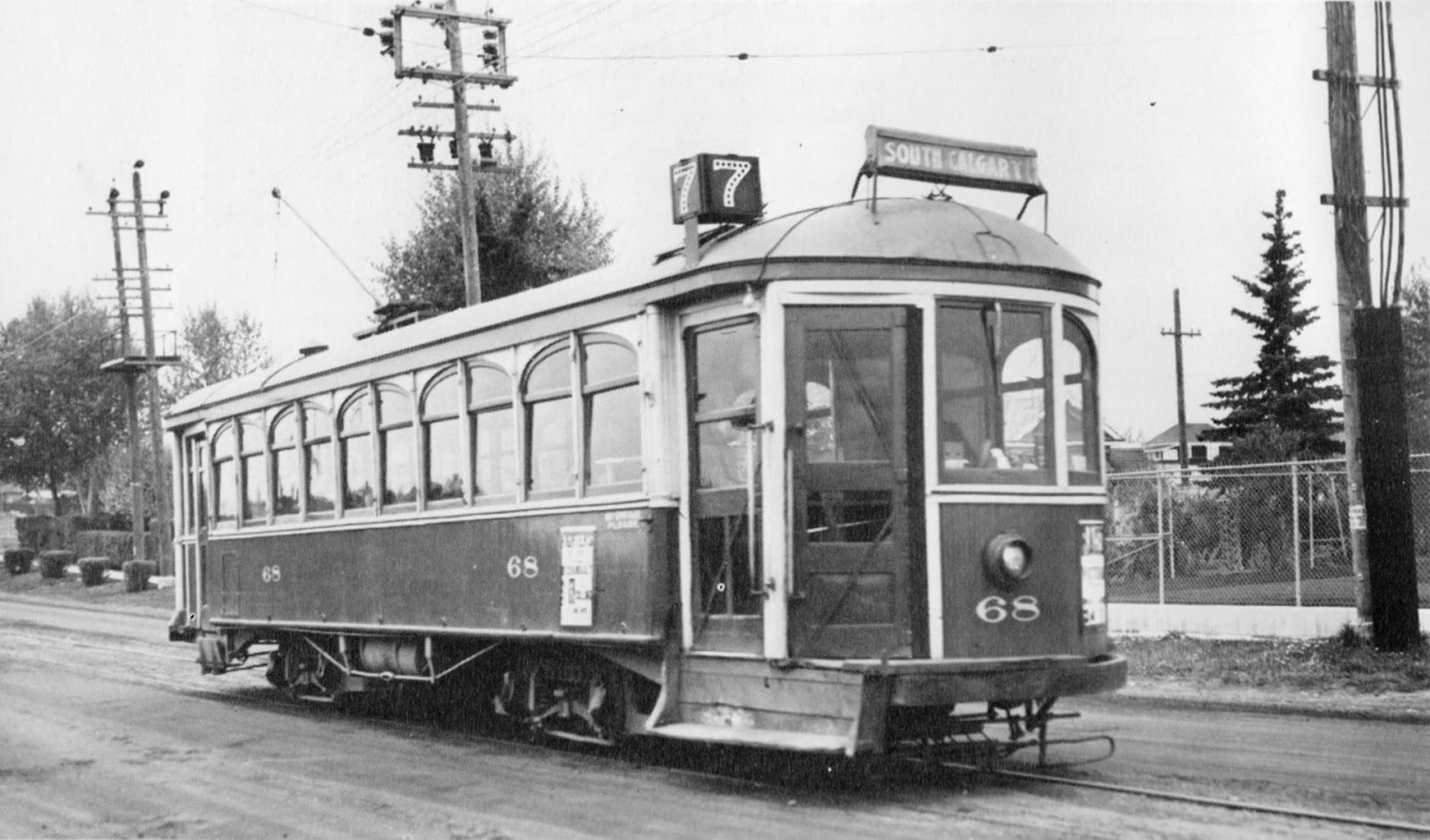

In 1909, 12 trams were launched in Calgary. At that time, the city’s first skyscraper was also built, which housed the Grain Exchange business center. The corporate development of downtown Calgary confirmed the need for public transportation, because ordinary workers could not afford personal transportation, so the appearance of streetcars became a lifeline for them.

The tram network was named “Calgary Electric Railway”. The final stop was at Stampede Park. The network was renamed the “Calgary Transit System” as early as 1946, when diesel and electric buses became popular. In the 1910s, the network expanded rapidly and by then already covered 5 lines. The final expansion took place in the 1920s. Routes were identified by color (blue line, white line, etc.), and in the 1930s numbers began to be used instead of colors to indicate routes.

In 1998, the documentary Calgary Remembered was released, where local residents who grew up around the time of the streetcars described the joy they felt at the new form of transportation. One Calgarian described how he held onto the back of the streetcar with his hand while following it on his bicycle. Yet another resident recalled how, due to a difficult financial situation, he split his ticket in half in order to ride the tram twice.

The areas of Marda Loop and Bowness developed due to the influence of the streetcar system. The Marda Loop area was a turning point on one of the tram lines, which contributed to its prosperity. But in the Bowness district, in 1911, the English lawyer and landowner of Bowness, John Hextall, built a bridge at his own expense. At that time, this land did not belong to Calgary. Hextall asked Calgary to run a tram line over this bridge to his complex. The city agreed, in exchange for which Hextall gave two Bowness islands for the city to use as a park. In 1948, Bowness was registered as a village, and 3 years later – as a city. In 1964, Bowness was assigned to Calgary.

During the Great Depression, buses instead of streetcars went to the elite Mount Royal area. The Second World War also prevented the modernization of the tram system. The last tram as a form of public transport on the streets of Calgary ran in 1950.

Bus connection

Gas-powered buses were launched in 1932 for residents who did not have access to trams. Electric buses and electric trolleybuses were also added in the early 1940s. Starting in 1950, they were gradually replaced by diesel buses, because the city of almost half a million people needed reliable and cost-effective transport.

Calgary’s bus connection has often been the subject of controversy and even strikes. In 1961, workers of the transport system took part in a 37-day strike. The union was unhappy that then-Mayor Harry Hayes had cut transportation costs amid inflation and refused to raise workers’ wages. After the strike, the city still raised the wages of transporters by 9 cents. In addition, in 1968, students protested against an increase in fares.

Since 1972, according to the Blue Arrow service, bus routes have had a limited number of stops to save time. Blue Arrow ceased to exist in 2000 and was later replaced by the BRT (Bus Rapid Transit) system.

The advent of CTrain

During Calgary’s 1967 transportation study, the idea to put a two-line subway system into operation came up. However, during the construction boom of the 1970s, the city invested almost all of its money in construction. They decided to build light rail transport (LRT), which is common in European and North American countries, instead of the subway. The system was called C-Train and later renamed to CTrain. Light rail transport is cheaper than the metro, because it can use the tram infrastructure and does not require the construction of tunnels. In the countries of the former USSR, such transport is called a high-speed tram, and if it has underground sections, it is called a metrotram.

On May 25, 1981, the 6.9-mile (10.9 km) South Line of the CTrain was extended from Anderson Road to 7th Avenue SW. This high-speed light rail system was one of the first in North America.

After 4 years, the Northeast Line was opened from Whitehorn station to the city center. The North West Line was opened in preparation for the 1988 Olympic Games. It ran from the city center to the University of Calgary campus. After that, all three lines were gradually expanded.

The main part of the network began to function as a light metro, and in the area of free travel in the city center, the red and blue lines – as a city tram. After some time, the design of a new green line was proposed, the central part of which would pass underground. Tunnels were built for this purpose, but later they refused to realize the project, because the city exceeded the planned budget by 23.3 million dollars.

In February 2008, the Calgary Herald ridiculed these tunnels, writing that they would remain a lonely shrine. At the time, the city authorities hinted that the tunnels would be used to expand the LRT, but did not give any exact dates.

Controversy and debate over the LRT extension continued. In 2010, Mayor Dave Bronconnier shied away from making a decision on the location of Sunalta’s West LRT station because he owned commercial property near the future station. As a result of its construction, the value of this property would increase by 15%.

Political conflicts also took place during the mayoral elections in 2017. Politician Bill Smith has advocated a review of the already approved Green LRT line, while provincial Infrastructure Minister Brian Mason said the project would not be funded if it was changed. In the end, they decided to build the green line, planning the completion of the first 15 stations in 2027.

In the first quarter of 2022, Calgary’s LRT was ranked as one of the busiest light rail systems in North America, with ridership exceeding 100,000 each weekday.